How has Benedictine education shaped you?

- Benedictine Sisters of Chicago

- Jul 11, 2024

- 10 min read

Updated: Dec 3, 2024

By Sr. Susan Quaintance, OSB

Sr. Susan Quaintance presented “Holy Conversation: Is that the Crux of Benedictine Education?” in September 2023, invited by the Sisters of Mount St. Scholastica Monastery, sponsors of the annual Fellin Lecture to support the liberal arts orientation of Benedictine College. Her lecture is below, with minimal edits to accommodate this printed format. It was originally published in the Spring 2024 edition of the journal Benedictines and then republished in the Winter/Spring 2024 Sacro Speco.

Any of you who have ever endured a pop quiz or slogged through a complicated lab or puzzled over a problem set or stayed up way too late to write a paper about a book you’re not sure you understood may have raised your eyebrows at the title of this talk. You may have thought, “Holy conversation? Really? On what planet did this woman go to school?” I feel you. Right in the thick of assignments and deadlines and exams, Benedictine academic life might seem like many things, but certainly not “holy conversation.”

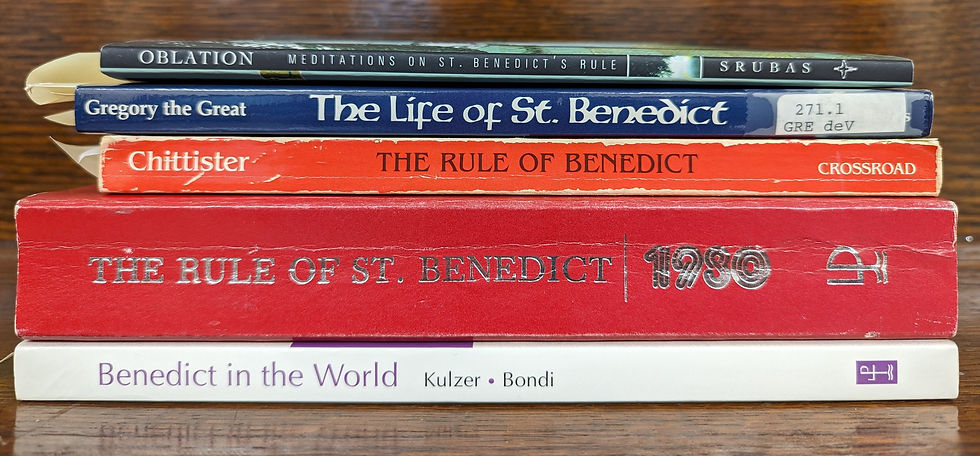

But I have a hunch that at its best, at our best, that’s exactly what it is. I stole that title from the wonderful story about Benedict and Scholastica in The Dialogues of St. Gregory the Great. Many people in this auditorium could recite the story by heart, but for those of you who don’t know it, I’ll tell it in brief. As was their annual custom, Benedict and Scholastica met between their monasteries one particular year to have a visit. St. Gregory writes: “They devoted the whole day to the praises of God and to holy conversation.” They talked into the evening, and then Benedict said it was time to leave. Scholastica asked him to stay so they could keep talking about holy things. He refused. So she put her head down on the table and, moved to tears, prayed. The skies opened up, and there was such a storm that Benedict couldn’t leave. Gregory concludes that part of the story with the words: “And so it happened that they passed the whole night in vigil and each fully satisfied the other with holy talk on the spiritual life.” They went back to their own monasteries, and Scholastica died three days later. She, too, had a hunch: one she listened to.

If I was going to give a lecture, though, in front of, well . . . you . . ., I felt like I better have something to back up my hunch. So I gathered some data. Disclaimer # 1: this data is unscientific and statistically irrelevant. But still: data.

For twenty-three years I taught at St. Scholastica Academy, the all-girls high school sponsored by my religious community, the Benedictine Sisters of Chicago. For most of my tenure there, we talked a lot about being a Benedictine school, what Benedictine values are, and what they look, sound, and feel like in practice. It seemed to me that women who went to that school should really be the ones to tell what difference a Benedictine education makes.

So I asked. I emailed about 100 alumnae who I had taught over the years (and had contact information for) and asked how the lens of Benedictine spirituality shaped their worldviews. The responses I got came from women who attended St. Scholastica between 1994 and 2013. They came from women in a wide range of vocations: social work, education (from primary teacher to college professor), customer service, analytics, entertainment. A nurse. A pediatrician. A farmer. A couple attorneys. Three of those who wrote back had gone on to Benedictine institutions of higher learning, including two "Ravens" who graduated from right here at Benedictine College.

Their responses were generous and thoughtful, and I am profoundly edified that these women took time out of their very busy lives to show up for an old nun. Certain themes came up over and over again, and those are the heart of my remarks tonight. These alums talked about how a Benedictine education sparked, nurtured, and sustained their empathy, curiosity, community-mindedness, balance, and contemplative spirits.

Deeply gratifying is how many answers spoke about empathy and how a Benedictine education taught the capacity to look at the world as someone else sees it.

Brittany said, “At SSA I was taught that loving Jesus meant loving and standing up for everyone, not just those who society deems worthy . . . I’ve never been afraid to have conversations about hard issues because I have always centered my work in love, something I definitely learned at [Scholastica].”

Jordan wrote: “SSA taught me the importance of seeing the world through the lens of another. [When I] move to a new place and explore new people and traditions – seeing how others live expands my worldview. It helps build my empathy and understanding.”

Diamond talked about how the stories of Benedict and Scholastica taught her about “loving others more than we love ourselves: sensing and being Spirit-led to ‘hear’ the unspoken needs of Jesus’s people.”

Mercedez said that a Benedictine education helped her “not to see things as black and white.” She went on to say that “instead of blaming, we need to ask where we can help.”

It taught Jennifer W. “to strive to help the broader community, even if we don’t know them.”

Katie learned “to look beyond myself; it’s how we treat each other in the dark times that matters.”

As I sat with these comments, I was intrigued by how much they reflected not just what we taught at St. Scholastica Academy in Chicago, but what I know students learn and practice at other Benedictine schools all over the world. How does that happen? It happens because these schools are so deeply grounded in the Benedictine tradition.

What these women said about empathy immediately brought to mind another story from The Dialogues of Gregory the Great in which Benedict, near the end of his life, sees the whole world in a single ray of light. Unpacking the theological implications of the event, St. Gregory says, “in the very light of the internal vision, the capacity of the soul is enlarged; it is so expanded in God that it is placed above the world. Indeed the soul of the seer is raised above itself.” Of course we find that empathy in the Rule of Benedict as well. Benedict teaches that his followers should always take special care of the most vulnerable: the sick, the old, the young, the poor, guests. And monastic people are always to be on the lookout for how they can serve each other. Empathy: seeing the world as God sees it.

Another thing that emerged in the emails I received was a love of learning that has enriched the respondents’ adulthoods.

Laura, one of the Ravens I mentioned earlier, said that Benedictine schools urged her to “discover things: ask questions and then go seek answers.”

Dejah talked about how Theology class, in particular, “allowed her to be curious, without being judged,” leading to a lifetime of healthy spiritual exploration.

Mary recounted that, “In the classroom our teachers taught us to ask questions. They urged us to look under the surface of what we were reading or studying, into a deeper inquiry, and ultimately a deeper understanding. We learned to push boundaries and think for ourselves.”

These thoughts, too . . . so very Benedictine. It’s no coincidence that the title of an essential monastic text is The Love of Learning and the Desire for God. The Rule of Benedict is rooted in a respect for and love of the word – both upper and lower-case “w.” Besides building a schedule where monks listen to scripture and pray the Psalms regularly throughout the day, Benedict dictates that there would be ample time for lectio divina (“holy reading”) and study. In Chapter 48, “On the Daily Manual Labor,” the word “read” is used 11 times . . . in just 24 verses. While Benedict encourages his monks (and later followers) to do “whatever work needs to be done,” he clearly thinks that study is just as important in a life of faith and meaning.

Nor surprising to any of you, I suspect, is how many of our alumnae raised the importance of community.

Laurencia, another Raven, said that that was a value that “strongly impacted” her. The sense of belonging that community provides “will motivate us to grow in relationship with God and others as we are all striving toward the common good.”

Mary, who we heard from before, observed that “At Scholastica it was all about community . . . What we did, we did together. Our teachers guided us not just with questions in class, but in questions about our lives – what do I desire to be and do? They encouraged us and enabled us as we tried new things, occasionally making fools of ourselves, but gaining confidence all the time. We learned to see in ourselves and each other what they already saw in us.”

Obviously, that fits easily into the larger Benedictine milieu. Benedict directs his teaching to cenobites, the kind of monks who live under a Rule and an abbot or prioress . . . together. The list of things that community members do together is long: praying, eating, receiving guests, welcoming newcomers, making decisions, stewarding property and possessions.

In order to live communal life well (whether in a monastery, family, or any other intentional community), one must learn a sense of balance.

Bridget reflected: “Going to a Benedictine school ingrained in me the importance of everything that goes into making people feel like whole humans. Not just a student, or athlete, or someone who is religious or spiritual, but how all those things intersect and often vie against one another for attention within ourselves. My Benedictine education [gave] me the opportunity to practice, during a critical time in my personal and brain development, how to honor the different pieces of myself and find ways to strike a balance as frequently as possible.”

Ann described it this way: “Some people seem to think one must choose one or two areas of interest . . . I’ve never been able to do that . . . balance and diversity bring me joy. I think of my true self as an artist and a farmer; engaging the body, mind, and great mystery, all supporting each other. The ability to pursue multiple things was always encouraged at SSA and the abbey [Belmont Abbey College].”

Benedict famously taught “moderation in all things” or something pretty close to that, which is probably the source of this Benedictine value of balance. He counsels avoiding the extremes in the daily schedule, food, speech, discipline – even prayer! I think we also see this in the Rule where no one is encouraged to be super-specialized. Benedict acknowledges that some people are better at some things than others, but generally, people aren’t exempted from jobs that keep the common life going. The artisan of the monastery still took (and takes) a turn at kitchen service. Guests are everyone’s responsibility, not just the porter’s or portress’s. When there is an important decision to be made, everyone must be consulted.

Finally, and perhaps most counterculturally, a Benedictine education supports the development of a contemplative spirit. It teaches one to be quiet, to listen.

Jennifer M. wrote: Of all the lessons I could share – the most notable that has shaped my worldview is listening with the ear of my heart. My Benedictine education taught me to bring mindfulness and quietness to life in being fully present and listening to God’s love as it’s the loudest sound . . . I learned this through practicing lectio, a repetition of a text that I’ve carried into my current career. My work uses the power of sport to foster positive social change in communities and for the last several years I’ve practiced this with incarcerated youth populations . . . The goal is to help the youth find a quietness and peace around just being – acceptance of past and direction for future. And every time I do it with them, I learn things about me. That’s part of listening – it’s a mutuality that is hard to capture on one side or a singular agenda.

Ann, the farmer/artist we heard from before, articulated it this way: “I find my love for silence supported and encouraged; I feel it is a great strength as an adult to be able to turn inward and lean on the quiet voice inside. A rich inner life is really the cornerstone to [being] an emotionally healthy human.”

It is not coincidental that these women were formed in a tradition whose foundational document begins with the words “Listen carefully.” While some of Benedict’s comments on silence simply reflect the teachings of his monastic forebears about silence as a discipline (which it is!), they are also much more. Being silent is a way to reverence what else is happening; it is key to attention. It allows for other voices – scripture, tradition, community – to be heard as prominently to the racket of our self-will, perhaps even as a counter to it. In one translation of the Rule, the first line of Chapter 42, “Silence After Compline,” reads “Monks should diligently cultivate silence at all times.” That word, “cultivate,” seems especially evocative. Like good gardeners, what might we grow in silence? Benedict knew that by feeding our souls a balanced diet, and not just dumping in anything that came along, good fruit would result.

Before I conclude – and I’m close – I do need to offer disclaimer # 2. In claiming that Benedictine education has something special to offer, am I saying that it is the only tradition that teaches women and men to think critically and pray wholeheartedly in preparation for lives of integrity, justice, compassion, and service? In the worlds of Eric Litwin, the creator of the awesome Pete the Cat children’s books, “Goodness, no!” Benedictines do not have the corner on empathy or silence or even community. Many, many schools – from their own values and traditions – provide exemplary moral education and supply avenues for its practical application. Thank heavens!

But I do want to return to my hunch about Benedictine education being holy conversation. Like the monastic body at prayer, creating a rhythm between one side of chapel and the other, my own experience of the truth of my hunch was confirmed by what my former students had to say, to teach: that the charism leads to an educational system that is conversational. It is a back-and-forth between students and teachers, students and other students, faculty members and administrations, schools and their sponsoring communities, schools and their local areas. It is a dialogue between people and ideas, and between ideas and ideas. I suspect that it is at the heart of the freshman Benedictine College Experience here. The best days in a Benedictine education are a palaver between play and rigor, sound and silence, the joy of learning something new and the discomfort of being stuck. Most critically it prepares minds and hearts for conversation with the One who created those minds and hearts and sends us out in service of the gospel. Being a part of that sacred exchange has been one of the great joys of my life; I hope you can say that, too. (If not today, some day.)

St. Benedict and St. Scholastica – pray for us!